Dutton LB1 and the Sources of Garci Sánchez de Badajoz1

B.W. Ife

It is a commonplace of literary studies that problems of text and

interpretation are really the same thing. Is Hamlet's 'too, too solid

flesh' really 'sullied'? Is Cressida 'the Trojans' trumpet' or 'the

Trojan strumpet'? While the poetry of Garci Sánchez de Badajoz is hardly

in Shakespeare's league, it nevertheless poses some interesting

challenges both to the editor and the critic. In common with many poets

of the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, Garci Sánchez's

poetry has not been transmitted in the form of neat compilations of

'collected works', but has to be assembled from numerous relatively

scattered printed and manuscript cancioneros.

2

The nature of these

sources creates complex problems for the production of a critical

edition, and the purpose of this study is to re-examine one of the

sources in particular, British Library Add. MS 10431 (Dutton LB1),

3

in order to reassess its authority as a source for Garci Sánchez, and to

use it to draw some wider methodological and interpretative

conclusions.

For a writer who was famed as a lunatic lover and spent at least part

of his life as a court poet, Garci Sánchez's extant corpus of poems is

fairly small. Altogether, some 66 poems have survived in 30 sources up

to 1520 (Table 1). The headline points are fairly obvious: the sources

which have the greatest number of poems by Garci Sánchez are the two

printed collections 11CG and 14CG (the first and second editions of the

Cancionero general, compiled by Hernando del Castillo and printed in

Valencia in 1511 and 1514), and the British Library MS now known as

Dutton LB1.

4

Understanding the relationship between these three early

sources is therefore central to determining their relative authority as

sources for Garci Sánchez and for many other poets represented in

them.

[See Table 2 in pdf file (22KB)]

British Library Add. MS 10431, formerly known as the British Museum

cancionero, is an important collection of some 470 pieces by 112 named

poets from the reigns of John II, Henry IV and the Catholic Monarchs.

5

It is a quarto volume currently consisting of 120 folios written in a

single hand, mostly in double columns. A second hand has added a small

number of comments and annotations. The MS may once have been longer,

since the rubric of fol 1r alludes to works by 'el famoso poeta' Pedro

de Herriega, which do not appear in the volume.

6

The date of the MS is

uncertain. Hugo Rennert estimated a date between the 1470s and 1500,

7

Carolina Michaëlis de Vasconcelos preferred 1500-1520,

8

Dutton estimates

'hacia 1500' (I,131), J. González Cuenca thought that it predated 11CG,

9

while Patrick Gallagher placed it between 11CG and 14CG (3- 5).

We have no record of ownership until the MS was sold by Sotheby's on

17 February 1836 from the library of Richard Heber to the British Museum

for the sum of one shilling. Two pieces of evidence led R.O. Jones to

conclude that the collection could have been the personal anthology of

Juan del Encina: a marked similarity between certain aspects of the

orthography of the MS and that of the 1496 edition of Encina's

Cancionero, above all the use of intervocalic

v rather than u; and the presence at the end

of the MS of a group of poems attributed to the 'actor deste libro'

among which there are two versions of poems from Encina's printed

collection together with at least one other which is very reminiscent of

Encina. Jones argued that the 'actor' ('compiler'?) was Encina himself.

10

Carlos Alvar has subsequently produced a helpful survey of the

relationships between LB1 and several other MS and printed collections,

and has been unable to escape the conclusion that LB1, 11CG and 14CG are

closely related, both textually and chronologically: LB1 and 11CG have

202 poems in common; 17 of those dropped from 11CG are in common with

LB1; and 19 of those added to 14CG are in common with LB1. 'LB1 presenta

composiciones que se encuentran sólo en 11CG, y que no volvieron a ser

publicadas en las ediciones posteriores, y también presenta otras piezas

que se incluyeron por primera vez en 14CG: parece que es lógico pensar

que LB1 es posterior a ambos Cancioneros impresos.'

11

While it is impossible to disagree with this conclusion as far as it

goes, there is a case for questioning the assumption (which Carlos Alvar

does not make, but which might easily be drawn from his conclusion) that

chronology and authority are necessarily causally related. Put simply:

is the authority of LB1 any weaker because it appears to postdate 1514?

Let us turn some of the earlier figures around: of the 1033 poems in

11CG, 831 (80.4%) are not in LB1; if the compiler of LB1 used 11CG, how

is it that 19 poems are included which appeared for the first time in

1514? And if he used 14CG, how is it that he includes 17 poems which

were dropped after the first edition? Furthermore, how is it that of 191

poems in common with 11CG, and 189 in common with 14CG, there is only

one common sequence of four poems, one of three poems, and six pairs?

And is it possible to account for the presence of unique poems in the

midst of common groups without assuming a much more complex relationship

than that which is implied by Carlos Alvar's analysis?

These questions are important because the relationship between

cancionero sources on the one hand and editions of the work of

particular poets on the other is fundamentally an assymetrical one, and

the editorial practices involved are very different in each case. Almost

always, cancionero sources are compilations or anthologies, whether of

one or several writers. They are a record of an individual's or group's

interests, tastes and collecting habits, compiled at a particular place

and time.

12

By their very nature, then, the cancionero anthologies impose

uniformity on variety. The process of collection and selection is

normative in cultural and artistic terms, while the material processes

of preparing the anthology for presentation, private enjoyment or

publication result in a 'fair copy' which appears to be consistent in

look and feel. If we were able to look beneath the visual and editorial

uniformity at the surface, we would almost always find a ragbag of

sources drawn from different places at different times, displaying

conflicting orthgraphical and typographical conventions, and most

important, sources of widely divergent textual authority.

None of this is very different from the normal process of preparing

any work for publication; behind the smoothly printed surface lies an

agony of recensions, drafts, re-drafts, last-minute corrections and

second thoughts at final proof stage. What makes this observation

important in the case of cancionero sources is the warning it gives us

that no statement about the authority of a particular text in a

cancionero anthology can safely be applied to any other in that

collection. The texts of Palgrave's Golden Treasury, for example, are

just as likely to derive from an autograph presented to the compiler by

the poet himself as from a unreliable printed source which perpetuates

mis-readings from the first edition. The typography of the finished

collection, and Palgrave's own editorial conventions as well as those of

the publisher, would obscure those discrepancies from view.

The implications of this for editorial practice may be summarised in

Figures 1 and 2. Figure 1 is a simple representation of what normally

happens when one edits a text. There are one or more extant witnesses

whose relationship has to be established before a series of procedures

can be applied to the texts of the witnesses to attempt to establish the

lost archetype. What we do when evaluating cancionero sources is almost

exactly the reverse (Figure 2). We usually have one witness, which we

know, suspect or have reason to believe has been compiled from several

sources, all of which are lost. In order fully to evaluate the authority

of the witness, we have to try to reconstruct all of the missing

sources, or at least their relationship to each other and to the witness

we have. A less conventional form of stemma is required to express these

relationships, and an example is given in Figure 3.

Top of page

[See Figures 1 (106KB), 2 (22KB) and 3 (35KB)]

How can we get behind the blank wall of uniformity presented by the

cancionero text? A great deal of evidence about the process of

compilation can be gleaned from a close examination of the physical

characteristics of the MS. LB1 now consists of 120 leaves, written

throughout in a single legible but non-professional hand, and in a

single ink. The MS originally consisted of 124 folios, as is indicated

by the original foliation, of which numbers 13 to 16 inclusive have been

removed. They almost certainly contained the Liciones de Job of Garci

Sánchez de Badajoz ('Pues amor quiere que muera', Dutton 1769), since

the last poem on the verso of folio 12 is the beginning of a dedication

of the Liciones to a friend. The poem was presumably removed in

deference to a change of spiritual climate in the 1520s. This poem is

also largely missing from a MS now preserved in the University of

Salamanca (Dutton SA10b-95), from which four folios have also been

removed, except that in this case the censor omitted to remove the first

17 lines. The opening rubric of LB1 ('Aqui comiençan las obras de garci

sanches de vadajos con otras obras de algunos syngulares poetas') and

the concluding 'finnis deo gratias' suggest that, apart from the four

missing leaves, the MS is substantially complete.

The paper on which LB1 is written is unfortunately unwatermarked, but

an irregularity in the spacing of the chain lines makes it clear that it

was all made from the same pair of moulds and that presumably it was

bought as a batch for this particular purpose. There is also evidence to

suggest that the paper was made into a book before the MS was written.

The original format is difficult to establish, since when the British

Museum acquired the MS it was rebound and the leaves supplied with new

hinges and quired in 15 lots of eight. It is unlikely that it will ever

be possible to establish the original format with certainty, which is a

pity, since quiring in 4s would suggest a ready-made book, whereas

quiring in 2s need not. But it is noticeable that the final four leaves

are significantly less closely written than the rest of the book and

point to the copyist's possibly having some difficulty in filling his

prescribed length, and might also account for the addition of the poems

attributed to the mysterious 'actor'. Physical evidence, then, points

to, but does not prove, that the MS was written 'at a sitting', into a

loose or possibly bound batch of paper whose length had probably been

estimated to fit the job in hand, and that it was written with the

object of drawing together a disparate collection of material between

two covers. The MS does not suggest a collection in the process of being

formed or added to gradually over a long period of time.

More physical evidence of a slightly different sort is given by what

we can deduce from the copyist's working habits. The MS is written for

the most part in double columns: the only exceptions are some poems in

arte mayor where the format will only allow single columns, and a couple

of pages written in three columns where the verse is basically

hexasyllabic. There are two other exceptions which will be mentioned

later. For the most part, the copyist seems anxious to fill his page as

tightly as possible, and throughout the MS one has the impression of

never a wasted space. But from time to time the copyist has punctuated

his progress through the book by leaving small areas of blank space,

usually at the end of a page, but sometimes in the middle, so as to

divide, in effect, the collection into 34 sections. Sometimes the

division is reinforced by a change in the rubric; or by writing the

rubric across both columns; or by using the formula 'de x cancion' where

the 'de x' means that all the following poems until the first

attribution are by x; by the use of some formula such as 'comiençan las

obras de x'; or by the use of what passes for a 'florid' capital (eg.

fol 104r). The 34 sections of the MS are summarised in Table 2.

[See Table 2 in pdf file (22KB)]

Two alternatives are suggested by this unconsious ordering of the MS.

Does it represent an attempt to classify the material, and if so what

system of classification was used? Or do the divisions represent the

points at which the copyist changed his exemplar? In the first

alternative - the compiler or the copyist if they were not the same

person - might have taken his shuffled collection of odds and ends and

dealt them into piles corresponding roughly to a division by authorship.

This is quite possible, since changes of section never come in the

middle of a group attributed to one author, though some authors, for

example Pinar and his sister Florencia, are common to more than one

section. It is likely that the longest and most substantial sections

were put together in this way, since within the section one can detect

changes in the type of source, although these could well have been

present in the immediately preceding exemplar.

On the other hand, some divisions correspond more obviously to

particular sources, especially where a number of poets are grouped

around a particular theme or subject or are related geographically or by

period. Besides, the copyist sometimes indicates a change of author by a

florid capital within a section [90v-91r], and some of the sections

consist of a main author plus a fill-up, which would suggest that the

source might have been a MS or printed pliego with the characteristic

make-weight to fill out the extra space left by a longer work. In

another section the familiar tone of the attributions, the preponderance

of first names in the rubrics, suggest a group of domestic pieces

originating in one place at one time and recorded by one of their

number, or a secretary who knew them well and expected his readers to

share that familiarity. Some sections are little more than scraps, and

this impression becomes stronger in the final groups where the copyist

seems hard pressed to fill the remaining pages [119v-120r] and where the

attribution of all the pieces to the 'actor' is not entirely clear.

Although the realisation that the MS is organised in some not very

obvious way represents a considerable step forward in our study of the

collection, it is at the next stage that the major unknown quantities

enter the argument. If some at least of the divisions do represent

changes of source, it should be possible to be more precise about the

nature and status of these sources, provided we can be reasonably

certain that the copyist has given us an accurate record of what he saw.

To that extent, then, are any differences discernible from section to

section an accurate reflection of the state of the sources? To answer

this question would involve demonstrating that the copyist was or was

not an accurate worker, a task which is strictly speaking not possible

unless one has the original from which he worked. But it should be

possible to gain some indications without straying too far in the

direction of guesswork.

We need to know as much as possible about the scribe's orthographical

preferences, the relative strengths of his preferences for some forms

rather than others, his general attitude towards his exemplar, his

willingness to leave difficulties or irregularities unsolved or

alternatively his readiness to intervene with his own suggestions and

solutions: in short, some guide to the literalness of his mind. The

first source of such information is where a text appears twice in the MS

and where it can only have been copied from the same exemplar. For all

practical purposes this means places where the copyist has corrected

himself, such as Figure 4, where three lines of the poem 'O mi dios y

giador [sic]' (Dutton 0706) were copied at the wrong point in the poem,

have been crossed through and repeated at the correct position, 11 lines

later. The differences in orthography between the two appearances of

these three lines are trivial (que/que; alunbra/alunbra; y/e;

virgo/virgo) while the similarities are telling (the long final s in

'nos'; the spelling of 'gia'; the contraction of 'lacrimarum').

Furthermore, the rhyme scheme of the poem indicates that in each

instance there is a line missing.

|

Figure 4 (fol 10v, column b). The first three lines have been cancelled and are repeated in their correct place in the following

stanza. The rhyme scheme shows that in each case there is a line missing between ‘yn hac lacrimarum vale’ and ‘o clemens virgo

maria’.

[Click on thumbnail image for full view]

|

Top of page

Unfortunately, such relatively long examples are very rare. More

common is the opposite case where a poem is repeated but we can be

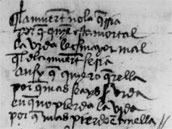

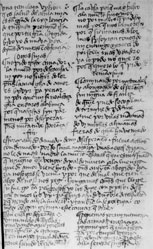

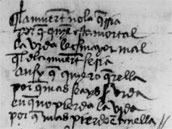

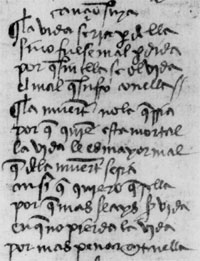

fairly sure that two different exemplars are involved. Figure 5 shows

two versions of the poem 'La vida seria perdella' (Núñez; Dutton 0843)

which appear on fols 43v and 44r. The orthography is virtually identical

until the last line, where the variant reading almost certainly

indicates a different source. Note the contracted final e on 'muerte',

which is a strong preference of this copyist. There are seven such

repeated pairs in LB1 and they can be quite helpful in gaining an

insight into the copyist's habits.

Figure 5 (fol 43v, columns a-b compared with fol 44r, column b). The orthography is virtually identical, but the variant in

the last line (‘porque mas pierdo en tenella’/’por mas penar en tenella’) points to two different exemplars.

|

|

|

| fol 43v, column b |

|

| fol 43v, column a |

|

|

|

| fol 44r, column b |

|

|

|

A further guide is provided by cases where a contrast in spellings,

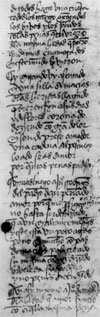

especially names, indicates a respect for both readings. Figure 6

illustrates a section of the text and commentary of Garci Sánchez's poem

'El dia infelix noturno' (Dutton 0731). Note how the lemma from the text

preserves the spelling 'tis', while the commentary gives the more

correct form 'Stix', and Figure 7 shows several examples of contrasting

pairs of spellings from the same poem: 'menalanpo/melampo';

'pamphago/panphago'; 'dorçeo/doçeo'. Note too the clue given by the

cancelled 'fueron' just before the poetic text resumes. These are clear

cases where spellings seem deliberately contrasted rather than being the

result of variation or carelessness: if the copyist knows that 'tis'

should be spelled 'Stix', then he could have changed it in the text of

the lemma. All the lemmata in this commentary show the same kind of

literal attitude to the text.

|

Figure 6 (fol 15v, columns a and b). The text (column a, sixth line) and the lemma (column b, first line) both read ‘hasta

que de tis laguna’, while the gloss reads ‘Stix’.

[Click on thumbnail image for full view]

|

A further source of information about the nature of the sources is

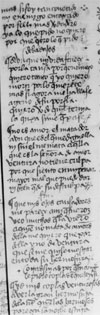

provided by those occasions where the copyist abandons his normal

working pattern, such as Figure 8 ('Caminando por mis males'; Dutton

0693), where the double-column format is abandoned in favour of the

common convention of writing the romance across the page. The mise en

page makes it clear that he prepared for this change of format by making

sure that the preceding poem ('No pido triste amador') finished in the

top half of the page, so that he could set off the cantar which is

included in the romance by reverting to double-column layout at the

bottom of the page. On the verso of this leaf he has the rubric 'torna a

romance' and resumes writing across the full width of the page. Only

four poems are written in this way, all are romances and all are in the

sections dedicated to Garci Sánchez de Badajoz, and they give a strong

indication that the copyist was trying to preserve the format of his

exemplar.

|

Figure 8 (fol 7r, whole page). The copyist made sure that the poem ‘No pido triste amador’ finished in column b, so that the

ensuing romance could be written across the page and the embedded cantar ‘Son en canpo desperança’ could be set off by reverting

to two-column format.

[Click on thumbnail image for full view]

|

I have already suggested that the abandonment of preferred forms,

especially strongly preferred forms, and the choice between forms in

free variation might also provide evidence of the original source. This

approach is suggested by the implications of textual critics working in

the field of the printed book, such as D.F. McKenzie's work on the

composition of The Merchant of Venice.

13

McKenzie demonstrates that when

Jaggard's compositor B abandons his preferred spelling he rarely does so

when his copy coincides with his preference, and when that preference is

very strong he never sets the alternative unless it is in the copy.

Applied over a wide range of examples, this study supports our intuition

that when a compositor has no preference he will tend to follow the

copy, and this observation might be expected to apply even more strongly

to a scribe than a compositor, since the scribe has fewer restrictions

caused by justification and the constraints of his fount, and is less

likely than the compositor to alter spelling to assist

justification.

Now although it is interesting to know the scribe's preferences, (and

in the case of LB1 we can say with some certainty that they are: hard

gi- and ge-; final -e; final -es; and final

long s, in descending order of strength) it is unlikely that these alone

will tell us much about the state of the exemplar, which is really what

we are interested in. But one feature which can tell us a good deal is

the type and degree of contraction present in a text, since there are

considerable differences in the use of contraction and ligatures by

scribes and compositors. For the scribe, the primary function of the

contraction is ease and speed of writing, though it could be and often

was used to assist in fitting a text into a given space. For the

compositor, the function of contraction is almost solely that of

justifying a line of type to the measure, and the range of its use is

constrained by the characteristics of the fount: he can only set the

ligatures which he has in his type cases. Inevitably, then, a

compositor's contractions can easily be distinguished from those of a

scribe, which tend to show a greater variety and density, and where we

find significant deviations from the copyist's norm in respect of

contractions, it is reasonable to look for a different kind of exemplar.

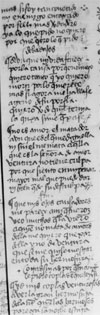

Figure 9 contrasts two columns of LB1. The left-hand column (fol 1va)

has 42 contractions, the second (fol 10ra) has 22. Note also the

different treatment of final -es/-es. The right-hand column

is part of a series of four poems which share the same characteristics

(see Table 3, below); the left-hand column is nearer the norm for this

copyist.

Figure 9 (fol 1v, column a compared with fol 10r, column a). The left-hand column has 42 contractions as against the 22 in

the right-hand column.

|

|

fol 1v, column a

[Click on thumbnail image for full view]

|

fol 10r, column a

[Click on thumbnail image for full view]

|

The final test of a copyist's attitude to his exemplar is the

surviving state of the texts themselves. At this point in the argument

it is convenient to concentrate on the section of the MS devoted to the

poems of Garci Sánchez de Badajoz, in order to bring together the two

threads of the argument: that it is dangerous to generalise about the

reliability of texts within an anthology; and that a close scrutiny of

the physical features of the collection, especially the accidentals, can

give some idea of the type of exemplar used and the extent to which the

copyist accurately reproduced what he saw before him. This section of

LB1 is also a good test because it raises in microcosm all of the larger

questions mentioned earlier about the relationship of LB1 to the first

and second editions of the Cancionero general.

Top of page

[See Table 3 in pdf file (35KB)]

Table 3 shows the order of poems by Garci Sánchez in LB1, 11CG and

14CG. It should be noted that six poems added in 14CG do not appear in

LB1 (seven, if the Liciones de Job, Dutton 1769, are included) and that

the only significant consecutive grouping common to LB1 and 14CG is 17,

(17a=9), 18, 19. These four poems are the same group of four which

showed a markedly lower density of contraction than the norm for LB1

(Figure 9), and which might therefore be supposed to have derived from a

printed source.

14

17a is an extra stanza which has been added to 17 in

the MS, but which is in fact the last stanza of the poem which occurs

between 17 and 18 in 14CG and which appears in full as no 9 in LB1.

Since this rogue stanza is headed 'fin' it seems likely that a massive

case of haplography has elided the two poems into one. As the evidence

of contraction suggests a printed exemplar, it is probable that these

four poems circulated in a printed pliego as a group and that they found

their way independently into LB1 and 14CG. It is unlikely that they were

taken from 14CG since poem no 17 and the rogue stanza do not appear on

the same page of the Cancionero general until the 1517 edition, and in

any case there is a major variant in the penultimate line.

Although the occurrence, or co-occurrence, of poetic texts in various

collections can be used to establish textual and chronological

relationships, there is a great deal more to be learned from detailed

study of the variants between these texts. One of the reasons which led

Patrick Gallagher to prefer CG readings to LB1 was the fact that,

although neither tradition, in his view, had more authority, the LB1

tradition was 'badly damaged in this sole surviving copy by inaccurate

and fragmentary transcription' (48). Carlos Alvar's subsequent

conclusion that LB1 postdates 1514 could be said to cast further doubt

on the reliability of the LB1 texts: if LB1 derives in some way from CG,

why are so many of the texts so different from each other? But the

implicaton that LB1 is a poor copy of CG is open to challenge when we

come to consider differentially the degrees of variation between LB1 and

CG from poem to poem. This raises an interesting question about rates of

decay in the transmission of texts, and could provide the editor with

another tool for investigating and elucidating the nature of a

cancionero anthology.

It is commonly accepted that every act of copying introduces changes,

some voluntary and some accidental. We might call this 'the law of

textual entropy'. But textual entropy is not constant; not all acts of

copying will introduce the same amount of change, so that there is no

such thing as a textual 'half life', a constant rate at which texts will

decay through successive copying. But it might be reasonable to expect a

single copyist who copies several texts under similar circumstances to

cause a much more constant rate of decay, even allowing for variations

in mood, tiredness, hunger and other working conditions. If MS A shows a

10% divergence from its supposed exemplar B, whereas another MS C shows

a 30% divergence from the same supposed exemplar B, we might question

whether C did indeed derive from B, or at least whether it derived via

the same route.

In the case of LB1 and CG, we find a range of divergence from poem to

poem of between 10% and 50%,

15

and it might be reasonable to ask whether

this wide range of divergence called into question whether all the MS

texts derived from printed exemplars, or indeed whether any of them did:

10% of lines with variants is in any case a high figure, as the rate of

variation between 11CG and 14CG, for example, which we know to be

directly related, is less than 1%. The importance of this line of

argument can be seen in Figure 10, where the 14CG text is longer than

that of 11CG and where the rate of divergence between LB1 and 14CG is

different in different parts of the poem:

|

|

ll. 1-34, 49-94 |

|

43/79 lines different (54%) |

|

|

|

ll. 35-48 |

|

8/14 lines different (57%) |

|

|

|

ll. 95-129 |

|

10/35 lines different (28.5%) |

|

|

[See Figure 10 in pdf file (46KB)]

It would be reasonable to conclude from this evidence that it is very

unlikely that whoever copied this poem into LB1 ever saw Castillo's

text, since the only possible hypothesis - that he already had the short

version and added the extra lines from Castillo, just as Castillo had

simply added extra lines to the 11CG version - is belied by the markedly

different rate of divergence between the two sections common to LB1 and

14CG. Since there are no variants between 11CG and 14CG in the sections

they have in common, we might assume that, rather than reprint the new,

longer text in its entirety, Castillo simply added the new lines at the

appropriate points in the 1511 text. This could affect any conclusions

which might be drawn from the above analysis of differential rates of

variation.

We should be wary, in any case, of imposing modern ideas and

expectations about textual transmission onto those of another period,

especially when we have no clear idea of what Castillo meant by

'ordenado y corregido por la mejor manera y diligencia que pude', and

when we note that he himself was aware of the lack of authority for some

of his texts: 'no fue en mi mano aver todas las obras que aqui van de

los verdaderos originales o de cierta relacion de los auctores que las

hizieron'. Yet Castillo's finished product is (like Palgrave's?)

visually very impressive and, by implication, authoritative. His texts

seem to be the longest, the tidiest and metrically the most consistent,

but are they hyper-correct by contrast with other sources?

Furthermore, it will often not be possible to locate the 'verdaderos

originales' for the simple reason that the author never intended to

produce a finished product, but rather an open-ended scheme, which like

the music of the period and that of today, would take as many forms as

it had performances.

16

Such a scheme is that of Garci Sánchez's Infierno

de amores (Dutton 0662), which consists of a sequence of stanzas each

telling of the sufferings of the most famous poets of the period, and

ending with an injunction to any gentleman who feels excluded to write

himself a stanza. As this poem exists in at least five sources it is

possible to get an idea of the way in which it grew in response to Garci

Sánchez's invitation. In Table 4, 13*BI is a rare early pliego suelto

preserved in the Bibliothèque Nationale and assigned by Norton to

Cromberger, Seville, 1511-1515, and SA10b is a late 15th-century

anthology now in the University of Salamanca. Note that SA10b is

complete in that, although it is the shortest, it has the stanza with

the invitation; that the series A-H is unlikely to be a response to the

publication of the invitation in 11CG since parts of it appear in two

other sources; that the group 10,14,24,29 is absent from all versions

except Castillo's; and the pairing 28+30 is common to all versions

except CG, since Castillo makes the Don Sancho of stanza 30 the brother

of Antonio de Velasco in stanza 29, whereas all the others make him the

brother of Diego de Castilla. The common sequences between LB1 and 13*BI

are very impressive and strongly indicate without recourse to variants

that LB1 does not in this case derive from CG.

Top of page

[See Table 4 in pdf file (38KB)]

Figure 11 shows just how cavalier the anthologist of 1500 could be

towards his texts. The Figures contrasts four stanzas from Garci

Sánchez's poem 'A la ora en que mi fe' (Dutton 0687) as recorded in LB1

and 11CG. Very few stanzas from the LB1 text of this poem retain

anything like the correct prosodic structure of the poem, and yet there

are very few places where the text does not make sense. The reason seems

to be that this is an example of memorial transmission, since what has

been lost is in almost all cases the structure of the stanza,

particularly the second half of each. Most stanzas preserve something

like the tight formal arrangement of the first six lines - abc, abc -

but the second part with its two quebrados has been elided into a

straight prose account of the sense. This is almost certainly because of

the rarity of the form (Le Gentil notes only six examples) which seems

to have been enough to defeat someone who had not seen it written down.

It is most unlikely that the text could have been reduced to this

condition had it been copied from a written, still less printed, source.

Yet the loss of the prosodic structure does not in itself render the

text useless, since there is nothing to prevent the compiler having

captured the sense more accurately than Castillo's neater version; that

kind of evaluation can only be made by looking at the variants

themselves, and there are a great many to be taken into account.

17

[See Figure 11 in pdf file (20KB)]

It would be reasonable to draw a number of general and particular conclusions from this

discussion:

- cancionero texts are not homogeneous and any statement about the

textual authority of one poem will not necessarily apply to the

next

- it is vital to look below the surface uniformity of the anthology

to discern, as far as is possible, the variety of exemplars which

underlay the compilation of the collection

- although LB1 is more closely related to 11CG and 14CG than to any

other source, the differences are just as striking as the

similarities

- although LB1 may be more closely related to 14CG than to 11CG,

there is no clear evidence that LB1 postdates either 1511 or 1514

- LB1 was compiled from a wide range of sources, some oral, some MS,

and some printed

- some of those sources, probably the majority, predate CG and were

transmitted independently of CG

- no generalisations can be made about the relative authority of the

CG and LB1 traditions in the case of Garci Sánchez de Badajoz, and

probably other poets of the period, and decisions about the relative

authority of textual sources have to be made on a poem-by-poem

basis

- the evidence of the various text traditions of Garci Sánchez de

Badajoz suggests that there is a large degree of textual variation

between them

- the degree of textual variation found in Garci Sánchez's sources

could be evidence of: extensive circulation of much larger numbers of

MSS than those which have survived; oral and/or sung transmission;

relatively high degrees of mouvance (textual instability) and/or

remaniement (reworking)

18

- in evaluating printed sources (such as CG) as against MS sources

(such as LB1), care must be taken to avoid anachronistic assessments of

relative accuracy and authority, since the pressure towards

normalisation inherent in printed media may have led to hyper-correction

during the preparation of texts for the press.

Finally, Table 5 summarises my own best estimates of the likely

sources of the Garci Sánchez poems in LB1.

[See Table 5 in pdf file (26KB)]

[See all tables in downloadable Excel file (77KB)]

Top of page

|